Published Ryan Schonert on February 21, 2019

Looking at the Volatiles in Tape Adhesives with Static Headspace GC-VUV

Although most of my current work at VUV revolves around gasoline analysis using ASTM D8071 GC-VUV, I’m always interested in seeing what else our technology can do. Because of my background in forensics, I especially enjoy exploring applications that could assist in criminal investigations. Most people are familiar with the popular areas of forensic science, such as DNA, drug analysis, or firearm examination, but something like the analysis of a tape sample could be critically important for an investigation. For example, imagine that someone committed a crime during which a victim was bound with duct tape; if the tape used on the victim could be matched to a roll of tape in the suspect’s possession, an investigator may be able to use this as part of the case. Conversely, finding that the sample doesn’t match the suspect’s roll could also be useful information.

Generally, tape samples are examined under the microscope for their physical characteristics. However, it’s also possible to identify the chemicals used in the tape’s adhesive, and this can provide useful information to investigators. Even if the tape can’t be chemically fingerprinted to a brand or specific roll, a chemical analysis could relate or distinguish tape samples from each other, which may guide the investigation in the right direction. Tape can be chemically analyzed using solvent extraction or pyrolysis with GC, but I wanted to know: what compounds could we see using static headspace-GC with a VUV detector?

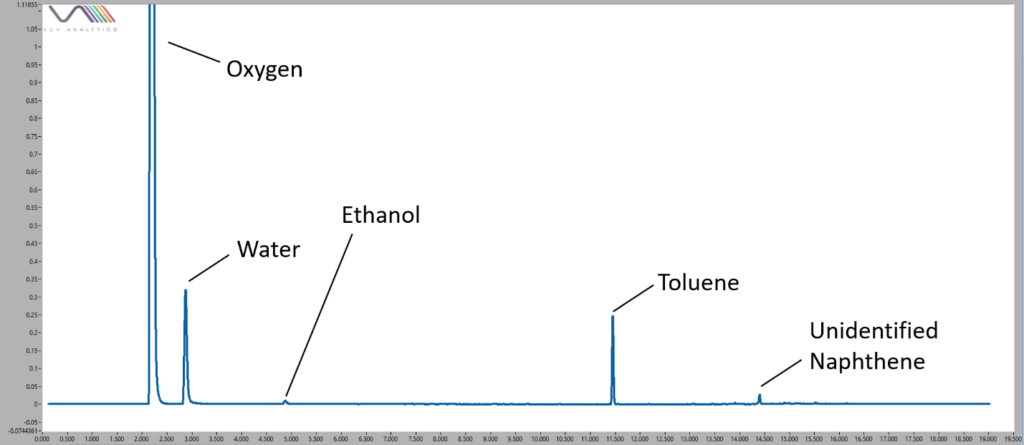

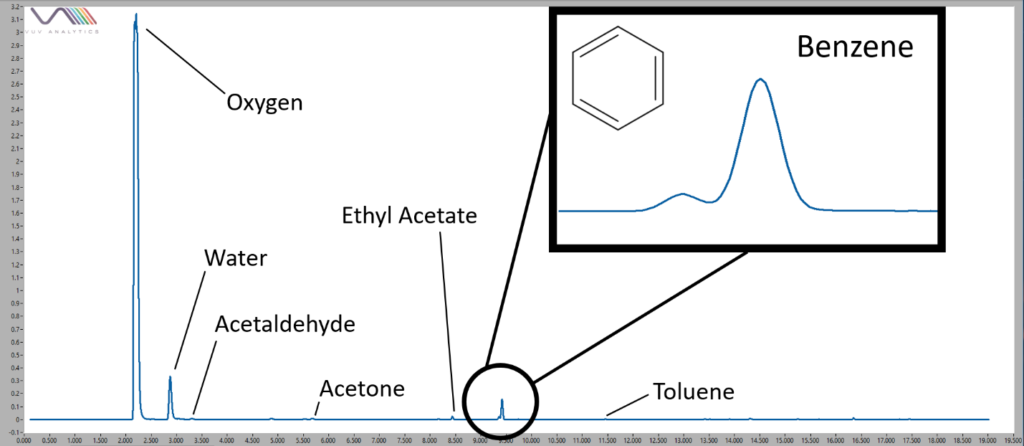

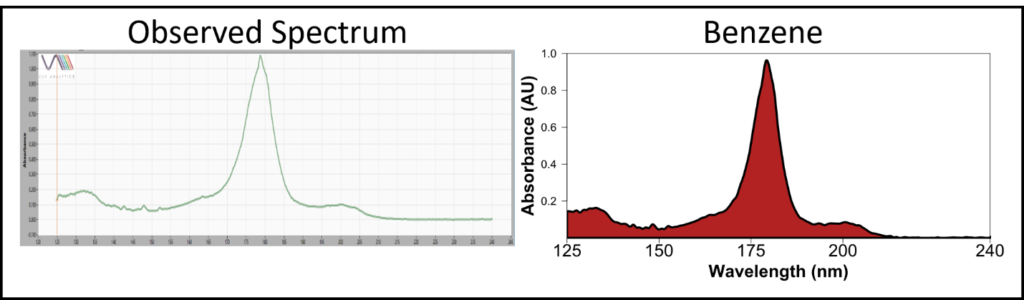

After collecting some duct, packing, and electrical tapes, I placed strips of each in headspace vials. I had the samples incubate for 15 minutes at 150°C, then I injected them for a 20-minute GC run. Figure 1 shows an example chromatogram from duct tape. Each sample gave off various levels of solvents and other hydrocarbon compounds, identified through their unique absorbance spectra, and these were enough to distinguish them from each other in this basic study. However, the packing tape sample had something surprising that the other samples didn’t – benzene, which was present in a large amount (Figures 2-3). Considering benzene’s high toxicity, this was a very interesting find!

Figure 1. Volatile compounds found in a sample of duct tape. Oxygen and water are commonly seen as background components in headspace analyses, but peaks such as the large toluene peak distinguished this sample from the others.

Figure 2. Volatile compounds found in one brand of packing tape. Only 1 of the 5 brands of packing tape gave a large benzene peak, distinguishing it from the other tapes.

Figure 3. The VUV absorbance spectrum observed at 9.5 minutes in the analysis of a packing tape sample matches benzene in the library. Thankfully, benzene was only observed at high headspace incubation temperatures, so packing tape likely isn’t a health hazard at ambient temperature.

Since the benzene came specifically from one sample of packing tape, I was curious if I would see the same thing in packing tape samples from other brands. So, I gathered packing tape samples of 4 other brands and repeated my analysis. As it turns out, none of the other packing tape samples had this benzene peak, meaning it was specific to the first brand I analyzed.

Don’t worry though, the packing tape in your house won’t poison you with benzene. I redid the experiment, but I had the tape incubate at a more moderate 50°C (122°F) instead of 150°C. Thankfully, I couldn’t see any compounds other than oxygen and water from the air, so even an extremely hot Texas day won’t bring out much benzene from this tape.

This simple headspace GC-VUV analysis may not be groundbreaking in the forensics world, but it shows that VUV spectral identification can be applied to many areas other than gasoline. The VGA-100 and VGA-101 are great general-purpose detectors – give something new a try, and you might just be surprised at what you find!

Leave a Reply